Unraveling Mesopotamia's Social Fabric: Hierarchy And Daily Life

The Cradle of Civilization: A Complex Society

Mesopotamia, often referred to as the cradle of civilization, was home to one of the earliest complex societies in human history. Its fertile crescent provided the ideal conditions for settled agriculture, leading to surplus food production, which in turn allowed for specialization of labor and the growth of urban centers. As these city-states expanded, so too did the need for organized governance, resource management, and social control. Did the rise of Mesopotamian civilization hinge on its intricate social structure? The answer is a resounding yes, as this complex hierarchy shaped every facet of life, from resource allocation to legal justice, and was fundamental to its stability and prosperity. At its core, the social structure of ancient Mesopotamia was hierarchical, with distinct classes that determined an individual's status and role within the community. This stratification wasn't arbitrary; it evolved out of necessity, creating a system where each segment of society, from the highest echelons to the lowest, had specific roles, responsibilities, and privileges essential to the functioning of society. The Mesopotamian social hierarchy basically consisted of three broad classes: nobility, free citizens, and slaves, though within these, further distinctions created a nuanced pyramid of power and influence. Understanding these classes helps us grasp the complexities of ancient Mesopotamian society and its remarkable achievements.The Apex of Power: The King

At the very pinnacle of the Mesopotamian social hierarchy stood the king. The king was the top rank holder, wielding supreme authority over the entire city-state or empire. Their position was not merely political; it was deeply intertwined with religious beliefs, making them the ultimate temporal and spiritual leader. The king, nobility, and the priests who stood on the top of the social pyramid formed the uppermost stratum of Mesopotamian society, but the king's power dwarfed all others.Divine Authority and Royal Responsibilities

The authority of the Mesopotamian king was considered divine. They were believed to be literal gods on earth or, at the very least, divinely appointed representatives of the gods, acting as intermediaries between the heavens and humanity. This sacred connection legitimized their rule and instilled a profound sense of awe and obedience among the populace. This divine mandate meant that the king was responsible for creating the laws, ensuring justice, and maintaining cosmic order. Famous examples, like the Code of Hammurabi, illustrate the king's role as the supreme legislator and judge, establishing a comprehensive legal framework that governed daily life and reinforced social distinctions. Beyond their legal and religious duties, kings were also the head of the army. They led their forces into battle, defended their territories, and expanded their empires through conquest. Military prowess was a crucial aspect of kingship, demonstrating strength and ensuring the security and prosperity of their people. Furthermore, the king oversaw massive public works projects, including the construction of temples, irrigation systems, and city walls, all vital for the well-being and defense of the city-state. Their immense responsibilities underscored their pivotal role in the functioning and survival of Mesopotamian society.Symbols of Status and Wealth

The king's exalted status was visibly manifested through their opulent lifestyle and distinctive attire. They used to wear a lot of jewelry made up of gold and had nice clothing, adorned with precious stones and intricate designs that symbolized their wealth, power, and divine connection. Their palaces were grand, sprawling complexes, far exceeding the size and luxury of any other dwelling, reflecting their unparalleled position. These material symbols were not just for personal comfort; they served as powerful visual reminders of the king's supreme authority and the hierarchical nature of Mesopotamian society, reinforcing the social order in the minds of all citizens.The Pillars of Society: Priests and Nobility

Directly beneath the king, forming the upper class alongside royalty, were the priests and the nobility. This elite group held immense power and influence, serving as crucial intermediaries between the divine and the human, and managing vast resources that underpinned the Mesopotamian economy. The social structure of Mesopotamia was hierarchical and divided into three main classes: Upper class, middle class, and lower class. The upper class consisted of royalty, priests, and the nobility, signifying their elevated status and control over significant aspects of society.The Sacred Role of Priests

The priests formed the next most powerful group after the king. In a deeply religious society like Mesopotamia, where every aspect of life was believed to be influenced by the gods, the role of priests was paramount. They were the guardians of the temples, which were not just places of worship but also major economic centers, owning vast tracts of land, managing workshops, and controlling trade. Priests were responsible for performing elaborate rituals, interpreting omens, offering sacrifices, and ensuring the favor of the gods for the entire community. Their proximity to the divine granted them immense spiritual authority and considerable material wealth. Beyond their religious duties, priests also played a significant role in education, particularly in the training of scribes, and in the administration of temple lands and resources. They were often scholars, astronomers, and healers, contributing to the intellectual and scientific advancements of the era. Their influence permeated daily life, from agricultural cycles to legal judgments, making them indispensable to the social and spiritual well-being of the city-state.The Influence of the Nobility

The nobility comprised high-ranking officials, military commanders, wealthy landowners, and members of the royal family. These individuals often inherited their status or earned it through distinguished service to the king. They controlled significant resources, including large estates and numerous laborers, and held key administrative positions within the government and military. Their wealth and connections afforded them considerable privileges, including access to education, luxurious homes, and fine goods. The nobility served as a vital support system for the king, assisting in governance, leading military campaigns, and managing the vast bureaucracy. While they did not possess the divine authority of the king or the spiritual power of the priests, their economic and political influence was substantial. They formed a powerful elite that helped maintain order and stability, acting as a crucial link between the royal court and the broader population. Their existence underscored the stratified nature of Mesopotamian society, where birthright and proximity to power determined one's standing.The Backbone: Scribes and Merchants

Beneath the king, nobility, and priests were the scribes and merchants, who occupied a crucial position in the social hierarchy of Mesopotamia. While not possessing the same level of inherited power or divine connection as the upper echelons, their specialized skills and economic activities were indispensable to the functioning and prosperity of Mesopotamian society. They formed a significant part of what could be considered the "middle class," bridging the gap between the ruling elite and the common populace.Scribes: Keepers of Knowledge

Scribes held a unique and highly respected position in Mesopotamian society due to their literacy. In a world where writing was a complex and specialized skill, scribes were the select few who could read and write cuneiform, the wedge-shaped script developed by the Sumerians. Their training was rigorous and lengthy, often beginning in childhood at temple schools. This mastery of writing made them indispensable to every aspect of administration, law, and commerce. Scribes were responsible for recording laws, compiling historical annals, drafting contracts, managing temple inventories, and conducting correspondence. They served in royal courts, temples, and private businesses, acting as record-keepers, accountants, and legal clerks. Their ability to document and preserve information was fundamental to the sophisticated governance and economic activities of the city-states. The prestige associated with literacy meant that scribes often came from wealthy families, as the cost of education was high, but their skills could also lead to upward mobility for talented individuals.Merchants: Engines of Commerce

Merchants were another vital component of the Mesopotamian middle class. With limited natural resources like timber, metals, and certain stones, Mesopotamia relied heavily on trade to acquire necessary materials. Merchants facilitated this vital exchange, undertaking perilous journeys across vast distances to bring back goods from distant lands such as Anatolia, the Levant, and the Indus Valley. They traded local agricultural surpluses, textiles, and manufactured goods for timber, copper, tin, gold, silver, and precious stones. These entrepreneurs played a critical role in the economic life of the city-states, contributing to their wealth and cultural exchange. They managed caravans, negotiated prices, and navigated complex trade routes, often accumulating considerable personal wealth and influence. While they might not have held political office, their economic power was undeniable, and their activities were crucial for the prosperity and technological advancement of Mesopotamian civilization. Their success underscored the importance of commerce in shaping the dynamic social hierarchy of Mesopotamia.The Common Touch: Free Citizens and Artisans

The vast majority of the Mesopotamian population comprised free citizens, often referred to as commoners. This broad category included farmers, fishermen, shepherds, soldiers, and various artisans. The social structure in ancient Mesopotamia was hierarchical, with kings and priests at the top, followed by nobles, commoners, and slaves. The free citizens formed the backbone of society, providing the labor and goods necessary for the entire system to function. Farmers, who constituted the largest segment of this class, were the primary producers of food. Their tireless work in cultivating the fertile lands along the rivers provided the agricultural surplus that sustained the urban populations and allowed for specialization of labor. They were often organized into collective work groups, especially for large-scale irrigation projects, which were vital for agricultural success in the arid region. While they owned their land or leased it from temples or nobles, they were obligated to pay taxes in the form of crops or labor. Artisans, including potters, weavers, metalworkers, carpenters, and jewelers, were skilled laborers who produced essential goods for daily life and luxury items for the elite. They often worked in workshops attached to temples, palaces, or as independent craftspeople, selling their wares in the bustling city markets. Their craftsmanship contributed significantly to the material culture and technological advancement of Mesopotamia. Soldiers, meanwhile, were responsible for defending the city-state, serving under the command of the king and nobility. Their service was crucial for maintaining peace and protecting trade routes. These free citizens, while not enjoying the luxuries of the upper classes, possessed certain rights and freedoms under Mesopotamian law. They could own property, engage in legal contracts, and participate in community affairs, albeit with limitations based on their status. Their lives were often challenging, marked by hard labor and vulnerability to natural disasters or warfare, but their collective efforts were indispensable to the survival and flourishing of Mesopotamian civilization.The Foundation: Slaves and Their Plight

At the very bottom of the Mesopotamian social hierarchy were the slaves, who constituted the lower class. Their lives were marked by hardship, limited rights, and often brutal conditions, yet their labor was a fundamental component of the Mesopotamian economy, particularly in large-scale projects and domestic service. Individuals could become slaves through several means. War captives were a primary source, as defeated enemies were often enslaved and brought back to the victorious city-state. Debt was another common cause; if a free citizen could not repay their debts, they or members of their family could be forced into temporary or permanent servitude. Children born to enslaved parents also inherited their status. Unlike some later societies, Mesopotamian slavery was not primarily based on race or ethnicity but rather on circumstance. Slaves performed a wide range of tasks. Many toiled in the fields, working on temple lands or large private estates, contributing to agricultural production. Others were involved in construction projects, hauling bricks and materials for temples, palaces, and city walls. A significant number served as domestic servants in the homes of the wealthy, performing household chores, cooking, and caring for children. Some skilled slaves might have worked as artisans or in other specialized roles, but their output belonged to their masters. While their lives were undoubtedly harsh, Mesopotamian law did grant slaves some limited protections. They could, in some cases, own property, engage in trade, and even marry free citizens (though their children would typically be slaves). There was also the possibility of manumission, where a slave could buy their freedom or be granted it by their master, often through long and loyal service. Despite these occasional avenues for improvement, the vast majority of slaves lived lives of subservience, forming the essential, yet often invisible, base upon which the entire elaborate social structure of Mesopotamia rested.How the Hierarchy Maintained Order

The intricate social structure of Mesopotamia was not merely a static arrangement of classes; it was a dynamic system designed to maintain order, ensure stability, and facilitate the functioning of a complex society. How did the social hierarchy function in Mesopotamia? It operated through a clear delineation of roles and responsibilities, reinforced by legal codes and religious beliefs, creating a framework where each class understood its place and contribution. Mesopotamia social structure defined distinct roles and responsibilities for each citizen that shaped Mesopotamian society. The king, at the top of the social hierarchy, exercised ultimate authority, backed by divine mandate and military might. This centralized power ensured swift decision-making and enforcement of laws. What roles defined each social class in ancient Mesopotamia? Each stratum, from the priests who managed the sacred economy to the farmers who fed the populace, had specific duties that were vital for the collective good. This specialization of labor, enabled by the hierarchy, maximized efficiency and productivity. What distinguished social classes in Mesopotamian city-states was not just wealth or privilege, but also legal standing and social expectations. The Code of Hammurabi, for instance, explicitly details different punishments and compensations based on the social status of the perpetrator and the victim, clearly illustrating the legal distinctions between the upper class (awilu), commoners (mushkenu), and slaves (wardu). This legal framework served to reinforce the existing social order, discouraging challenges to the established hierarchy. The social structure in ancient Mesopotamia was hierarchical, with kings and priests at the top, followed by nobles, commoners, and slaves. This structure helped maintain order and stability by providing a clear chain of command, distributing labor effectively, and justifying the existing power dynamics through religious doctrine. The interdependency of the classes—the king needing the priests for divine favor, the priests needing the farmers for sustenance, the farmers needing the soldiers for protection—created a cohesive, albeit rigid, system. This system minimized internal conflict by assigning everyone a defined role and ensuring that essential societal functions were performed, thereby contributing to the enduring success of one of humanity's earliest and most influential civilizations.The Enduring Legacy of Mesopotamian Social Structure

The rise of Mesopotamian civilization undeniably hinged on its intricate social structure. This complex hierarchy shaped every facet of life, from resource management and legal justice to religious practice and military organization. The very concept of an organized society, with specialized roles and a clear chain of command, found its early and robust expression in the lands between the two rivers. The lessons learned from managing such a diverse and stratified population laid groundwork that would influence subsequent civilizations for millennia. The administrative innovations, legal codes, and urban planning that emerged from Mesopotamia were direct consequences of its hierarchical social organization. The need to manage vast temple estates, collect taxes, administer justice, and maintain public works necessitated a sophisticated bureaucracy, staffed by educated scribes and overseen by diligent nobles. The very idea of codified law, as exemplified by Hammurabi, arose from the necessity of regulating interactions within a multi-tiered society, ensuring that distinct classes had their rights and responsibilities clearly defined. The legacy of the Mesopotamian social hierarchy extends beyond its immediate impact. Elements of its stratified system, such as the concept of a divinely appointed ruler, the influential role of a priestly class, and the use of specialized labor, can be observed in various forms in later ancient civilizations, from Egypt to the Indus Valley, and even in some aspects of classical Greek and Roman societies. Mesopotamia provided a foundational model for how large-scale human societies could organize themselves to achieve collective goals, manage resources, and maintain stability over long periods. Its contributions to the development of societal norms and governance continue to resonate, offering invaluable insights into the origins of complex human organization. In conclusion, the social hierarchy of Mesopotamia was far more than a mere arrangement of people; it was the dynamic engine that powered one of history's most pivotal civilizations. From the supreme authority of the king, believed to be a literal god on earth, to the vital labor of slaves, each tier played an indispensable role in the grand tapestry of Mesopotamian life. This intricate stratification allowed for unprecedented levels of specialization, organization, and stability, paving the way for monumental achievements in law, administration, science, and art. The enduring insights we gain from understanding this ancient social fabric remind us of the profound impact that societal structure has on human progress and the enduring legacy of Mesopotamia as the true cradle of civilization. What aspects of ancient Mesopotamian society intrigue you the most? Share your thoughts in the comments below, or explore our other articles on ancient civilizations to continue your journey through history!

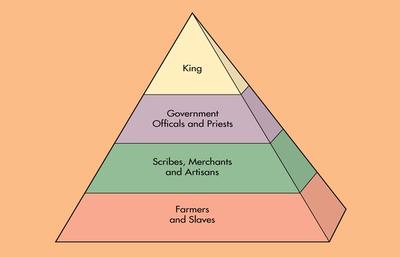

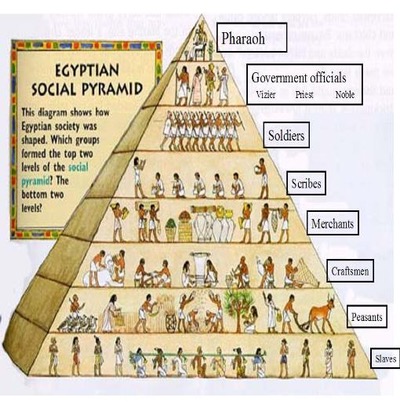

Social Structure Of Mesopotamia

This pyramid shows the social classes of Mesopotamia. This shows the

Social Hierarchy Of Mesopotamia