Unveiling Mesopotamia's Social Structure Pyramid

Step back in time to the cradle of civilization, a land nestled between the Tigris and Euphrates rivers, where some of humanity's earliest cities flourished. This ancient world, known as Mesopotamia, wasn't just a hub of innovation in writing, law, and agriculture; it was also a complex tapestry of human interaction, meticulously organized by a distinct social hierarchy. Understanding the Mesopotamia social structure pyramid is key to grasping the daily lives, aspirations, and challenges of its inhabitants, from the powerful kings to the countless laborers.

Imagine a society where every individual had a predetermined place, their roles and responsibilities intricately woven into the fabric of the community. This wasn't a static arrangement; it was a dynamic system that evolved over millennia, yet its fundamental principles of order and stratification remained remarkably consistent across various Mesopotamian cultures, be they Sumerian, Akkadian, or Babylonian. The intricate social class pyramid of Mesopotamia illustrates this complex societal structure, offering fascinating insights into how power, wealth, and status were distributed and maintained in one of the world's earliest and most influential civilizations.

Table of Contents

- The Foundation of Mesopotamian Society

- Visualizing the Pyramid: A Hierarchical Framework

- The Apex of Power: Kings and Priests

- The Middle Strata: Scribes, Merchants, and Artisans

- The Broad Base: Farmers, Laborers, and the Lower Class

- The Lowest Tier: Slaves in Mesopotamian Society

- Women in the Mesopotamian Social Structure

- Land Ownership and Economic Dynamics

The Foundation of Mesopotamian Society

Ancient Mesopotamia was a land of burgeoning urban centers, where populations varied greatly depending on the city and era. For instance, around 2300 BCE, Uruk boasted a population of approximately 50,000, while Mari, located further north, was home to about 10,000 people, and Akkad had a substantial 36,000 residents (Modelski, 6). These bustling populations weren't homogenous; they were carefully divided into social classes, much like societies in every civilization throughout history. The very organization of ancient Mesopotamia was dictated by their status, using a social structure pyramid as its guiding principle. This stratification was primarily organized based on people's wealth, influence, and inherited status, creating a clear and often rigid social order.

Visualizing the Pyramid: A Hierarchical Framework

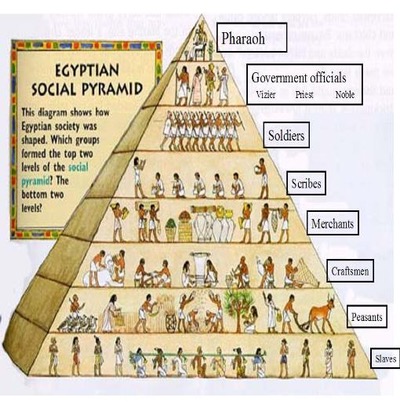

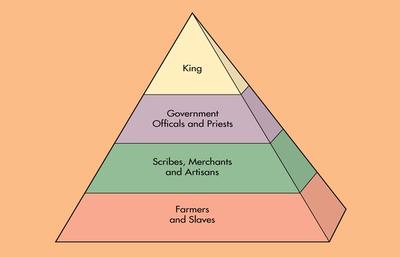

The hierarchy of Mesopotamia can be symbolized as a triangle-shaped pyramid, a visual representation that perfectly encapsulates its highly stratified nature. This social pyramid of ancient Mesopotamia consisted of several distinct layers, each representing different social classes and their corresponding roles, responsibilities, and privileges essential to the functioning of society. The social class pyramid of Mesopotamia can be visualized as a hierarchical structure, with the ruling elite firmly positioned at the top and slaves occupying the very bottom. This structure played a crucial role in the daily lives of Mesopotamians, influencing everything from legal rights to marriage prospects. The social pyramid of Mesopotamia can generally be divided into four or five primary layers, each representing a distinct social class, though some analyses simplify it to three fundamental categories: nobility, free citizens, and slaves. This hierarchy is crucial for understanding the dynamics of power and social mobility, or lack thereof, within this ancient civilization.

The Apex of Power: Kings and Priests

At the very pinnacle of the Mesopotamia social hierarchy pyramid stood the king. The king was the top rank holder, embodying both political and often religious authority. These rulers were not merely administrators; they were seen as intermediaries between the gods and humanity, responsible for the welfare and prosperity of their city-states or empires. Their power was immense, extending to lawmaking, military command, and the administration of justice. Alongside the king, and sometimes even predating the full emergence of kingship, the high priests held significant sway. In early Sumerian city-states, the temple was often the central economic and administrative institution, making priests incredibly powerful figures. The upper class, therefore, comprised the kings, high priests, and other "bigwigs" – the elite families and powerful officials who advised the ruler and managed the vast temple and palace estates. Their lives were marked by luxury, influence, and a deep connection to the divine.

The Divine Right of Kings

The authority of Mesopotamian kings was often legitimized through divine endorsement. Rulers like Hammurabi of Babylon presented themselves as chosen by the gods to bring justice and order to the land. This belief system reinforced their position at the top of the social pyramid, making challenges to their rule not just political defiance but also a transgression against divine will. They oversaw massive public works, managed irrigation systems crucial for agriculture, and led armies in times of war, all under the perceived guidance of the pantheon. Their palaces were centers of administration, justice, and elaborate rituals, further solidifying their elevated status within the Mesopotamia social structure.

The Influential Priesthood

Even as kings gained prominence, the priesthood retained considerable power, particularly within the vast temple complexes. Temples were not just places of worship; they were economic powerhouses, owning vast tracts of land, employing numerous workers, and engaging in extensive trade. High priests and priestesses managed these significant resources, oversaw religious ceremonies, and interpreted divine omens. Their spiritual authority often intertwined with the king's political power, creating a dual leadership structure in many periods. The well-being of the city was believed to depend on the proper observance of religious rites, placing the priests in a crucial and respected position within the social hierarchy.

The Middle Strata: Scribes, Merchants, and Artisans

Below the ruling elite lay the vital middle class, the backbone of Mesopotamian urban life. This tier included scribes, merchants, and skilled artisans. Scribes, masters of cuneiform writing, were indispensable. They recorded laws, kept administrative records, managed trade contracts, and composed literary works. Their literacy granted them immense prestige and access to power, often serving as advisors to kings and priests. Merchants facilitated the extensive trade networks that brought essential goods, like timber, metals, and precious stones, into resource-scarce Mesopotamia. They were often wealthy and influential, traveling far and wide to conduct business. Artisans, on the other hand, were the skilled craftspeople – potters, weavers, metalworkers, jewelers, and builders – whose expertise was crucial for creating the material culture of the civilization, from intricate artworks to functional tools and magnificent architecture. These professions required specialized training and knowledge, granting their practitioners a comfortable, respected position within the social pyramid.

The Broad Base: Farmers, Laborers, and the Lower Class

The vast majority of the Mesopotamian population belonged to the lower class, primarily consisting of farmers and common laborers. Farmers worked the fertile lands, producing the food surplus that sustained the entire civilization. Their lives were often arduous, dictated by the rhythms of the seasons and the unpredictable floods of the rivers. They paid taxes in the form of crops or labor to the temple or the palace. Common laborers engaged in various tasks, from construction projects like ziggurats and city walls to maintaining irrigation canals. While they were free citizens, their lives were often characterized by hard work, limited resources, and vulnerability to famine or warfare. This broad base supported the entire social structure pyramid, making their contributions absolutely essential for the survival and prosperity of Mesopotamian society.

The Lowest Tier: Slaves in Mesopotamian Society

At the very bottom of the Mesopotamia social hierarchy were the slaves. Unlike some later civilizations, slavery in Mesopotamia was not primarily based on race. Individuals could become slaves through various means: as prisoners of war, as punishment for debts (debt slavery), or by being born to enslaved parents. While their lives were undoubtedly difficult and they lacked fundamental freedoms, Mesopotamian slavery had some unique characteristics. Slaves could sometimes own property, engage in business, and even buy their freedom. They performed a wide range of tasks, from domestic service in wealthy households to labor in agricultural fields, mines, or large-scale construction projects. Despite these limited possibilities for advancement, their status was the lowest, and they were considered property, subject to the will of their owners. The existence of this class underscores the highly stratified nature of the Mesopotamia social structure.

Women in the Mesopotamian Social Structure

The role of women in ancient Mesopotamia was complex and varied, often depending on their social class and the specific period or city-state. While the overall societal structure was patriarchal, women were not entirely without rights or influence. They could own property, engage in business, and even initiate divorce in certain circumstances. Priestesses held significant religious and economic power, particularly in the early periods. However, their primary societal role was often tied to the household and family, with marriage and childbearing being central to their lives. Mesopotamian epic literature gives various perspectives onto women and their social roles, offering valuable, albeit sometimes idealized or symbolic, insights.

Perspectives from Epic Literature

When we delve into ancient Mesopotamian epic literature, such as the Epic of Gilgamesh, the Epic of Creation (Enuma Elish), and the Descent of Inana, we gain fascinating, albeit sometimes ambiguous, insights into women's roles. For instance, the goddess Inana (Ishtar in Akkadian) is a powerful, independent deity, embodying both fertility and warfare, suggesting a recognition of female strength and agency. In the Epic of Gilgamesh, the prostitute Shamhat plays a crucial role in civilizing Enkidu, indicating a recognized, albeit stigmatized, social function. While these texts often portray women in relation to men (as wives, mothers, or lovers), they also depict figures with agency, wisdom

Mesopotamia Upper Class

Social Structure Of Mesopotamia

This pyramid shows the social classes of Mesopotamia. This shows the