Unveiling The Social Class Of Mesopotamia: Ancient Society's Pyramid

Table of Contents

- Unpacking the Social Class of Mesopotamia: A Foundation of Civilization

- The Hierarchical Blueprint: General Social Strata

- The Apex of Power: Royalty and the Upper Class

- The Backbone of Society: The Middle Class

- The Foundation: The Lower Class and Laborers

- The Enslaved: At the Bottom of the Social Pyramid

- Women's Roles: Beyond the Tiers

- The Enduring Legacy of Mesopotamia's Social Structure

- Conclusion

Unpacking the Social Class of Mesopotamia: A Foundation of Civilization

Mesopotamia, often hailed as the "Cradle of Civilization," witnessed the birth of some of humanity's earliest cities and organized societies. This transformation, spurred by the first agricultural revolution around 10,000 BCE, led humans to settle down, form governments, and, in doing so, establish complex social structures. The very concept of social class emerged as a major sign that a civilization had been established, moving beyond nomadic hunter-gatherer groups to settled communities with specialized roles. The populations of these nascent cities, though varying significantly in size, shared a common thread: they were all divided into social classes. This division wasn't arbitrary; it was a fundamental aspect of their societal organization, influencing virtually every aspect of life from politics to economics. Understanding the **social class of Mesopotamia** is akin to looking at the foundational blueprint of human societal organization, demonstrating that while technologies and cultures evolve, certain social dynamics, like the concentration of wealth and power, have remained remarkably consistent over millennia. Mesopotamian civilization, like any other society, had a definite social structure, far from a perfectly egalitarian ideal, featuring both powerful and powerless classes.The Hierarchical Blueprint: General Social Strata

At its core, the **social class of Mesopotamia** was highly stratified and hierarchical. While specific terminology and the number of tiers might vary slightly across different periods and city-states within Mesopotamia (like Sumer or Babylonia), the underlying principle remained consistent: a pyramid-like structure with a few at the top wielding immense power and wealth, and the vast majority forming the broad base. Broadly, the Mesopotamian social hierarchy can be seen through several lenses. Some models simplify it into three main classes: nobility, free citizens, and slaves. Others expand this into four main tiers: royalty, upper class, middle class, and lower class. There are even interpretations suggesting six distinct classes. What remained constant, however, was that birth was a major factor in determining social strata, meaning one's position was largely inherited rather than earned. This inherent stratification meant that opportunities, privileges, and responsibilities were unevenly distributed, shaping the daily lives of everyone within the society. This ancient Sumerian social classes and government structure laid the groundwork for future civilizations.The Apex of Power: Royalty and the Upper Class

At the very pinnacle of the **social class of Mesopotamia** resided the royalty and the elite upper class. These individuals held the reins of power, wealth, and religious authority, embodying the highest echelons of society.The King: Divine Authority and Governance

The king was undeniably the top rank holder in the Mesopotamian social hierarchy. His primary duties were extensive, encompassing the running of the government, making laws, leading the army, and often serving as the chief priest or being seen as divinely appointed. The monarch's authority was absolute, a reflection of the belief that their rule was sanctioned by the gods themselves. This divine connection further solidified their position at the apex of the social pyramid, making them not just political leaders but also spiritual guardians of their city-state. The stability and prosperity of the city often hinged on the king's perceived favor with the deities and his ability to maintain order and justice.Priests and the Elite: Guardians of Faith and Wealth

Directly beneath the king, or often intertwined with royal power, were the priests. These individuals held immense spiritual and often temporal power. They managed the vast temple estates, which were significant economic entities, controlled religious rituals, and interpreted the will of the gods. Their unique look and access to divine knowledge gave them a distinct and revered position within the social structure. Alongside the priests, the upper class also included wealthy landowners, high-ranking government officials, and affluent merchants. These individuals accumulated substantial wealth through land ownership, trade, and their positions within the state bureaucracy. They enjoyed significant privileges, including access to education, luxurious goods, and political influence. Their power was not just economic but also social, as they often formed the council of advisors to the king and participated in crucial decision-making processes that shaped the destiny of their city-state.The Backbone of Society: The Middle Class

The middle class in the **social class of Mesopotamia** represented a vital segment of society, bridging the gap between the powerful elite and the vast working population. This group comprised skilled professionals and those involved in the administration and commerce of the city. In Babylonian society, the *awilu*, a free person of the upper class, might sometimes encompass those with significant standing, but the distinction between upper and middle class often came down to the extent of their wealth and political power.Scribes: The Literate Elite

Among the most respected members of the middle class were the scribes. In a society where literacy was a rare and highly valued skill, scribes held a unique and indispensable position. They were the record-keepers, chroniclers, and administrators, responsible for documenting everything from legal codes and religious texts to economic transactions and literary works. Their ability to read and write cuneiform, one of the earliest forms of writing, made them essential to the functioning of government, temples, and businesses. Scribes were often educated in special schools and could ascend to positions of considerable influence, demonstrating that skill and knowledge could, to some extent, offer upward mobility within the rigid social hierarchy.Merchants and Artisans: Driving Economy and Craft

Merchants played a crucial role in the Mesopotamian economy, facilitating trade both within and between city-states. They dealt in goods ranging from agricultural products to precious metals and luxury items, often undertaking perilous journeys to acquire and sell their wares. Their success contributed significantly to the wealth of the cities, and prosperous merchants could accumulate considerable personal fortunes, sometimes blurring the lines between the upper and middle classes. Artisans and craftsmen, including metalworkers, potters, weavers, jewelers, and builders, formed another important segment of the middle class. These skilled individuals produced the goods necessary for daily life, as well as the intricate artifacts and monumental structures that characterized Mesopotamian civilization. Their expertise was highly valued, and they often worked for the temples, the palace, or wealthy individuals. While not possessing the political power of the nobility, their specialized skills provided them with a stable livelihood and a respected place within the community, contributing directly to the material culture and economic vibrancy of Mesopotamian society.The Foundation: The Lower Class and Laborers

The largest social class in the **social class of Mesopotamia** was the working class, which primarily comprised farmers, shepherds, fishermen, and hunters. These individuals formed the broad base of the social pyramid, their labor being absolutely essential for the survival and prosperity of the entire civilization. They lived predominantly in the city surroundings, tending to the fields and livestock that provided the food supply for the burgeoning urban centers. These laborers, though free, often lived a challenging existence, subject to the whims of nature, the demands of the state, and the dictates of their landlords. They cultivated crops like barley and wheat, herded sheep and goats, and provided the raw materials that fueled the Mesopotamian economy. Their work was physically demanding and repetitive, yet it was the bedrock upon which the entire elaborate structure of Mesopotamian society rested. In Babylonian society, this group was often referred to as the *mushkenu*, a free person of low estate, who ranked above slaves but below the *awilu* (upper class). They received payment for their work, but their opportunities for advancement were limited, and their lives were largely defined by their agricultural or manual labor.The Enslaved: At the Bottom of the Social Pyramid

At the very bottom of the **social class of Mesopotamia** was the enslaved population. These individuals, known as *wardu* in Babylonian society, possessed the fewest rights and were considered property, serving as the most vulnerable segment of the population. Their lives were characterized by forced labor and a complete lack of personal freedom. People could become enslaved through various means. War captives were a primary source, as defeated enemies were often brought back as slaves. Debt was another significant factor; individuals who could not repay their debts might be forced into servitude, sometimes even selling their children into slavery to clear their obligations. Criminals could also be enslaved as a form of punishment. Slaves performed a wide range of tasks, from arduous manual labor in fields and construction projects to domestic service in wealthy households. While some laws, like those in the Code of Hammurabi, provided certain protections for slaves (e.g., against severe abuse, or allowing them to own property or marry free persons under specific conditions), their fundamental status as chattel meant they could be bought, sold, or inherited. Their existence underscored the deeply stratified nature of Mesopotamian society, where the concept of a perfectly egalitarian society was far from reality, and the powerful exerted complete control over the powerless.Women's Roles: Beyond the Tiers

While the primary social classes were largely defined by economic status, profession, and birth, the roles of women within the **social class of Mesopotamia** present a more nuanced picture. Mesopotamian epics, such as the Epic of Gilgamesh, the Epic of Creation (Enuma Elish), and the Descent of Inana, offer various perspectives onto women and their social roles, indicating that their status could vary significantly depending on their social standing, family background, and individual circumstances. In general, women in Mesopotamia had more rights than in many later ancient societies. They could own property, engage in business, act as witnesses in legal proceedings, and even initiate divorce under certain conditions. High-ranking women, such as priestesses or members of the royal family, could wield considerable power and influence. For instance, priestesses of major cults held significant religious and economic authority. However, for the majority of women, their primary role was within the domestic sphere, managing the household and raising children. While they were integral to the family unit and the functioning of society, their public roles were often more limited than those of men. The epics reflect this duality, showing goddesses and powerful queens alongside more traditional portrayals of women in family settings. This highlights that while the class structure largely defined opportunities, gender roles also played a significant part in shaping an individual's place and influence within Mesopotamian society.The Enduring Legacy of Mesopotamia's Social Structure

The **social class of Mesopotamia** was a defining characteristic of this foundational civilization, playing a crucial role in shaping the dynamics of its society, influencing everything from politics to economics and daily life. The highly stratified nature, with its distinct tiers of royalty, priests, scribes, merchants, artisans, farmers, and slaves, established a blueprint for societal organization that would be echoed in countless civilizations to follow. Indeed, social life in many ways has not changed significantly in 4,000 years. The concentration of wealth and power in the hands of a few, the importance of specialized labor, and the existence of a disadvantaged class at the bottom of the social pyramid are themes that resonate through history, including in our modern world. Mesopotamia was not unique in its stratification; the social structures of Mesopotamia and Egypt, for instance, were similar in that they both had broad social class systems with many tiers of power, though differences existed in their specific manifestations. The establishment of clear social classes was, in fact, a major sign or factor that a civilization had been established. It reflected a society capable of producing a surplus, specializing labor, and developing complex administrative systems to manage its population and resources. The intricate hierarchy, with each group having specific roles, responsibilities, and privileges, was essential to the functioning of society, demonstrating how ancient communities organized themselves to achieve collective goals, from building monumental ziggurats to maintaining vast irrigation systems.Conclusion

The **social class of Mesopotamia** offers a fascinating window into the foundational principles of human societal organization. From the divine authority of the king at the apex to the tireless labor of farmers and the tragic plight of the enslaved at the base, Mesopotamian society was a complex, hierarchical system where each tier played a vital, albeit unequal, role. This ancient stratification, shaped by factors like birth, profession, and wealth, laid down patterns of social interaction, opportunity, and identity that would persist for millennia. Understanding these distinct social classes helps us grasp the complexities of ancient governance, economic systems, and daily life. It reminds us that while the specifics of power and privilege evolve, the fundamental human tendency to organize into stratified groups has been an enduring feature of societies since the dawn of civilization. What fascinates you most about the social class of Mesopotamia? Share your thoughts below, or explore more articles on ancient civilizations to uncover how these early societies shaped the world we live in today.

Share

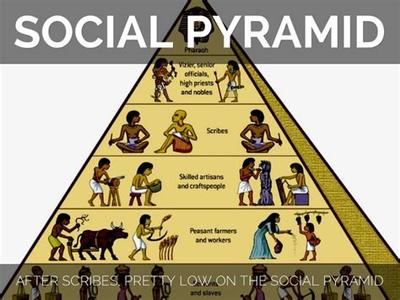

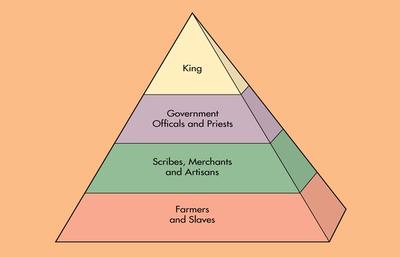

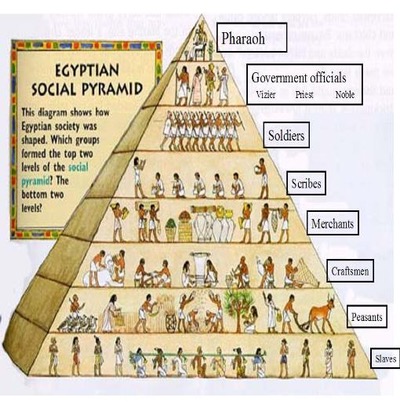

This pyramid shows the social classes of Mesopotamia. This shows the

Mesopotamia Upper Class